Defining art is, for sure, one of the biggest debate that has been going on for centuries. Throughout all its history, art was associated with beauty and morality. It was only after Modernism that art started to detach from our everyday life experience and, as explained by Nicholas Alden Riggle (2010), the ‘artistic significance was to be found solely in a work’s aesthetic, largely visual, formal properties, not its representation, social metaphorical, or political content’. Thanks to Post-modernism, art finally affirmed as anything that can ‘provoke an aesthetic emotion’ (Berger, 1988) and ‘that works as a vehicle used by human beings to communicate and express emotions and ideas through formal and informal elements’ (Bekar, 2015).

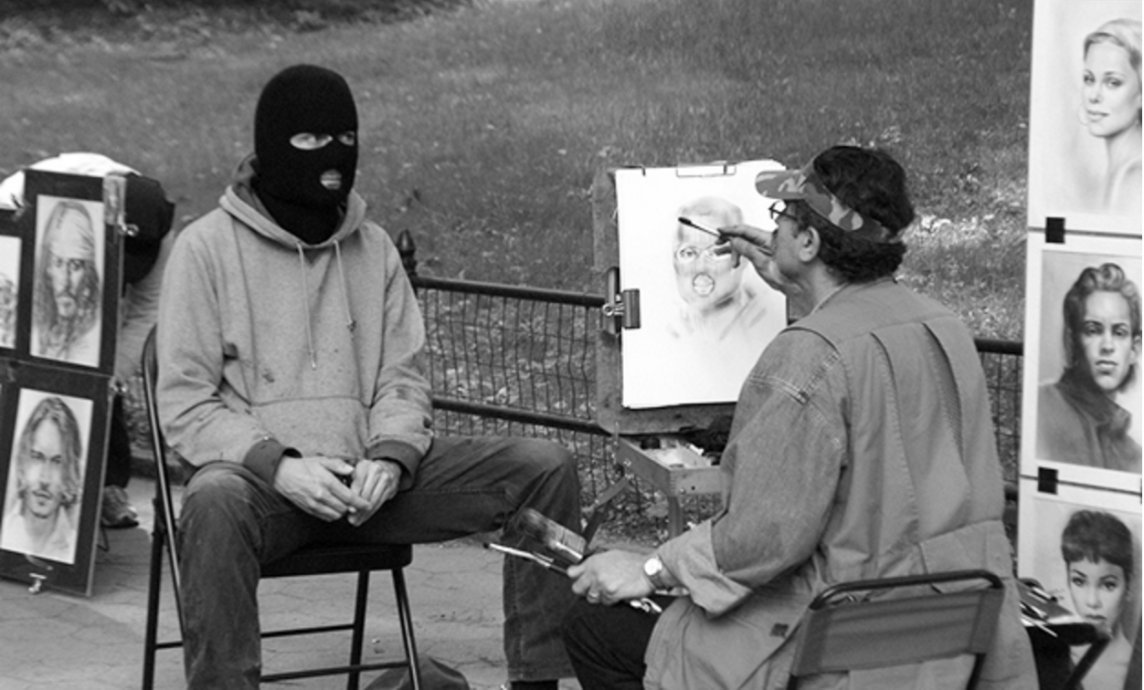

In this context, street art arose as the new and most impactful kind of art that surrounds our everyday life even if we are not conscious of it. This type of art is what Riggle defines as ‘post-museum art’, which is characterised by ephemerality, anonymity and disconnection from the art world. Street art is a controversial kind of art since it is often associated with acts of rebellion or of vandalism. Nevertheless, street art is different from those simple graffitis ruining monuments and buildings. Artists like Banksy, who uses his art as a ‘tool for communicating views of dissent, asking difficult questions and expressing political concerns’ (Wooters Yip, 2010), transformed the street art into a powerful mean of communication which is, thanks to its location, available to everybody. Street art can be defined as the very first form of modern art being democratic, for its availability and simplicity of the material used; as well as collaborative since it involves the participation not only of the artists but also of the viewers who, with their action, contribute, together with changes in the surroundings, in altering its form if not completely destroying it. ‘The purpose of street scrawls, murals and masterpieces is to exist within the everyday development of the place they inhabit. Street art isn’t intended to survive – the clue is in the name’ (Iqbal, 2010).

Nevertheless, the street is not the only sufficient element to define a piece of art as ‘street art’. It could be argued in fact that advertisings, like posters or billboards, or commercial art exhibited in the street could be named forms of street art, just because of the location in which their set. Although, this is not the case: the real ‘street art employs the street as an artistic resource’ so that the ‘artistic use of the street [becomes] internal to its significance’ (Riggle, 2010).

The use of the street, which is considered to be of everybody’s property, as already mentioned, causes this kind of art to be associated with illegality and vandalism, and this phenomenon is the reason why many street artists choose to be anonymous. Anonymity is, therefore, another key element which distinguishes street art from institutional art. Invader, a street artist who define himself ‘undefined free artist’ (UFA), famous for reproducing pixellated characters from the video game ‘Space Invader’ around the world, once said: ‘I can visit my own exhibitions without any visitor knowing who I really am even if I stand a few steps away from them’.

On the contrary, not every street artist choose the anonymous signature and Ben Wilson, also known as the Chewing Gum Man, is a demonstration. The artist is famous for using chewing gums, which pedestrian had been thrown on the street, as his canvas on which he creates colourful miniatures. Wilson, whose works can be found mainly on the Millennium Bridge, wholly embraces the essence of the street. ‘I am transforming rubbish.’ – Explains The Chewing Gum Man – ‘People are bombarded by images with so much consumerism around us. It is stuff they are buying or things they feel they have to have. […] I transform something that has been rejected by society’. His small artworks, from being simple chewing gums, are elevated to forms of art outcome of the collaboration of the artist, the viewers and the environment. The heart of his production is represented by the evolution of the piece: from being chewed, the gum is then thrown away on the street where it exsiccates and becomes the canvas onto which the artist can express himself. Afterwards, the artwork is subjected to being stepped on by pedestrians and eventually disappears.

For its intrinsic link with the street, which contributes to the meaning and the aspect of the artworks, street art cannot be related to cultural institutions and, most important, can’t be taken from the street. Nevertheless, we are already assisting at the new ‘public appetite and fashion for the [street art]’ and at how ‘graffiti has gained ground in galleries. And art shops. And Amazon. Works by Banksy, stencilled on shop walls, walkways and railway bridges, are reverentially being preserved behind sheets of Perspex’ (Iqbal, 2010).

The street artist Blu, whose identity remains hidden, decided to cover all his artworks in the city of Bologna with grey paint in reaction to the removal of those artworks realised on buildings about to be demolished. The cultural institution in charge of this decision thought of creating an international exhibition entirely dedicated to street art, entitled ‘Banksy & Co’ artist’s works. Opened on the 18th of March, at the price of 13 euros per ticket, the exhibition created many controversies among street art’s creators and appreciators.

The street artist Blu, whose identity remains hidden, decided to cover all his artworks in the city of Bologna with grey paint in reaction to the removal of those artworks realised on buildings about to be demolished. The cultural institution in charge of this decision thought of creating an international exhibition entirely dedicated to street art, entitled ‘Banksy & Co’ artist’s works. Opened on the 18th of March, at the price of 13 euros per ticket, the exhibition created many controversies among street art’s creators and appreciators.

The impulsive reaction of Blu was explained by the artist himself on his blog with the following words: ‘Blu is not in Bologna anymore, not until the magnates will keep on eating’. The artist was broadly accused of having deprived the city of his art, an act that was defined by the critics as an ‘art-war‘ against the art dealers and their policies.

In front of the accusation of having destroyed the meaning behind those artworks, the association Genus Bononiae, which directed the exhibition, responded that those pieces were illegally created in a private space and that, consequently, it is their right to buy the space and make use of those works.

The fight against the capitalism personified by those institutions which speculate on art has no limits and street artists, like Blu or Banksy, keep fighting their impositions and dogmas, even if that means removing all their works. As described by the collective of writers, Wu Ming, in a war might happen to sacrifice the beauty in change of the effectiveness of the action. It might be painful although, if done with the awareness that nothing can be achieved without sacrifices, even destroying years of beauty and art can be justified as valid.

What Blu and all the street artists remind us is that art is not only enclosed in the artwork itself. Art is the outcome of the love that unifies us as people, together with technology and nature. Art is life and the relations we build in this short time that we are given and that unfortunately still remains out of the dominant logics.

Bibliography:

- Iqbal, N. (2010). Not all art is meant to last for ever. The Guardian. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/feb/12/banksy-art-graffiti [Accessed 21 Mar. 2016].

- Ming, W. (2016). Blu, i mostrificatori e le sfumature di grigio. Internazionale. Available at: http://www.internazionale.it/opinione/wu-ming/2016/03/18/blu-bologna-murales-mostra [Accessed 21 Mar. 2016].

- Ming, W. (2016). Street Artist #Blu Is Erasing All The Murals He Painted in #Bologna – Giap. Wu Ming Foundation. Available at: http://www.wumingfoundation.com/giap/?p=24357 [Accessed 21 Mar. 2016].

- Smargiassi, M. (2016). Street writer Blu destroys his works in Bologna in fight against “private predators”. Repubblica.it. Available at: http://bologna.repubblica.it/cronaca/2016/03/12/news/street_writer_blu_destroys_its_works_in_bologna_in_fight_against_private_predators_-135316522/#gallery-slider=135312292 [Accessed 21 Mar. 2016].

- Wooters Yip, E. (2010). What is Street Art? Vandalism, graffiti or public art. Art Radar Journal. Available at: http://artradarjournal.com/2010/01/21/what-is-street-art-vandalism-graffiti-or-public-art-part-i/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2016].